Levels of Attention

Canadian ambient music producer Tim Hecker played live in Calgary last month. I only found out a few days in advance, but was fortunate enough to secure a ticket last minute. Although Hecker’s music is sparse and experimental, his live shows have the reputation of being immersive and loud as hell. Not something that I wanted to miss.

Philip Sherburne gave a nice overview of Hecker’s music in his review of 2016’s Love Streams:

His work is sculptural in feel and widescreen in scope, and it is extraordinarily attentive to texture. Foremost among his concerns has been the idea of diffuseness, of dissolution. There are few hard edges, few identifiable motifs; musical events, like a shift in tone or the introduction of a new timbre, often take place under the cover of static. He prefers distant shapes with vague outlines.

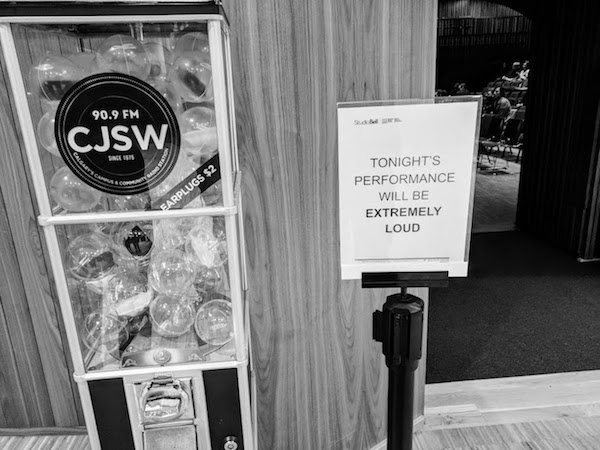

A few hours before show time, I received a message from the venue with a some words of caution. The performance would be loud enough to warrant hearing protection, and take place in total darkness. The second part caught me off guard.

Many of the electronic acts I have seen live have incorporated a visual component. Playing electronic music live lacks the sheer kinetic energy of a rock show. Projected video or generative graphics can serve as a replacement for this missing motion component.

Playing in darkness could be interpreted as a challenge to the necessity of this graphical accompaniment. A more likely explanation is that there was a logistical issue with Hecker’s lighting rig and the venue, so he simply decided to perform without. Either way, playing in darkness seems decidedly on-brand for a Tim Hecker show.

When the lights went down, the venue was not completely dark. Two exit signs on either side of the stage radiated red light. When anyone left the room, light entered through the doorway and cast long shadows.

Hecker played for a over an hour with no pauses between songs for applause. Extended periods of continual drone music in near darkness do interesting things to the brain. My mind wandered and I drifted—decoupled from reality. I have never been in a sensory deprivation tank, but I reckon it is a similar feeling.

In the liner notes of Music for Airports / Ambient 1, Brian Eno theorized that there is a versatility inherent to ambient music.

Ambient Music must be able to accommodate many levels of listening attention without enforcing one in particular; it must be as ignorable as it is interesting.

The usual level at which I interact with ambient music does not involve total darkness and excessive volume. Most of the time, I listen when I am working. Lyric-free electronic music helps me concentrate. As I’ve gotten older, multitasking has become more difficult. Trying to juggle context between work and anything more dense, like a podcast, is impossible.

The website musicForProgramming offers an explanation of how certain types of music can aid focus.

Music possessing [certain] qualities can often provide just the right amount of interest to occupy the parts of your brain that would otherwise be left free to wander and lead to distraction during your work.

The implicit minimalism of ambient music allows it to act as a kind of mental scaffolding. The level of engagement dictates the structure formed. Although other genres of music can be appreciated on many levels, ambient music is unique in its formlessness. From a blanker slate, the scope of possibilities is larger.

Further listening

It took a while for the ambient side to click for me. If you have hesitated in the past, give one of these records a chance. They are all fine listening for working on a project, reading in the bath, or as the soundtrack for a long nap.